Les municipales are go!

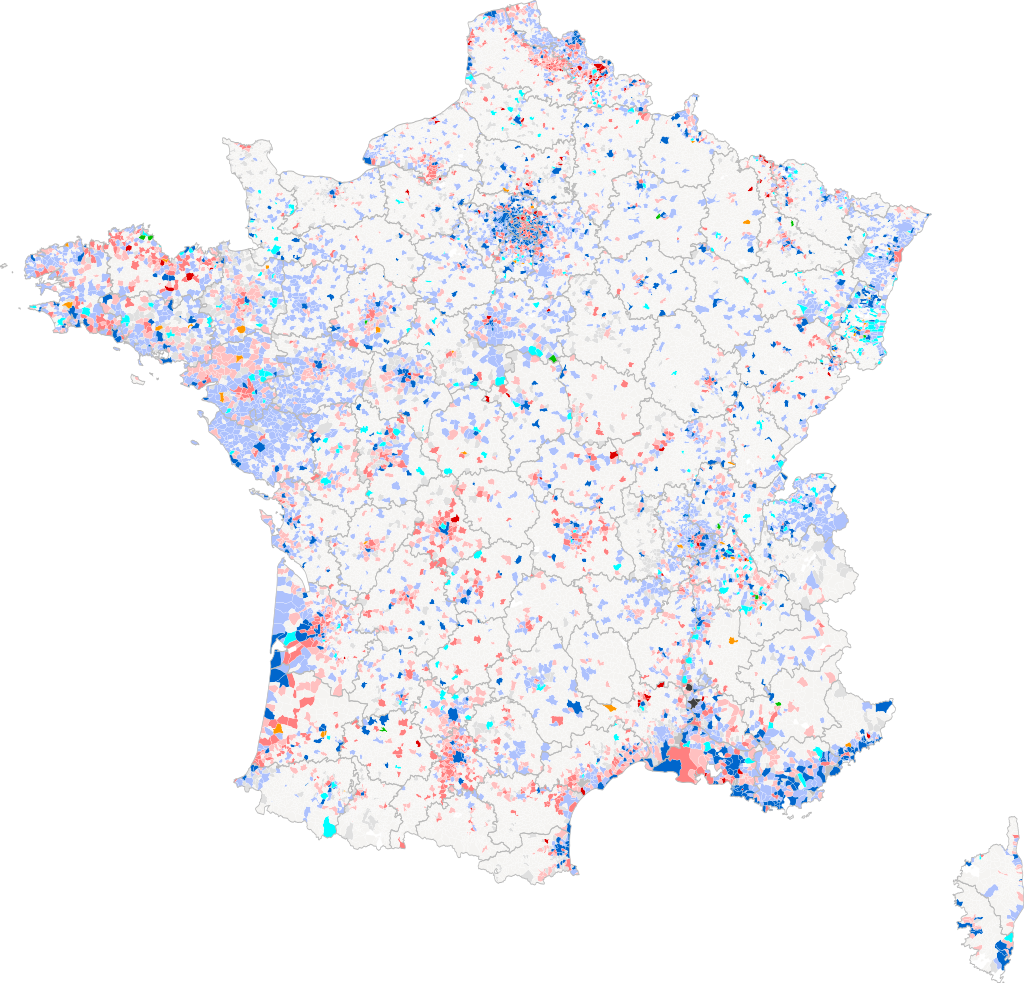

2014’s French municipal elections showing the results for larger communes

So, despite announcing to a TV, radio and online audience of nearly 25 million on Thursday evening a raft of measures to combat the coronavirus COVID-19, Emmanuel Macron has decided that the municipal elections in the 34,968 communes of mainland and overseas France will go ahead on 15 and 22 March. Before his address, there had been speculation that they might be put back, but according to various sources, leaders of the moderate right, including the speaker of the Senate (Gérard Larcher) and the chair of Association des Maires de France (François Beau-Gosse Baroin) made forceful objections. (A suggestion that Laurent Fabius, chair of the Constitutional Council also had a hand in changing Macron’s mind was denied via the Council’s Twitter account on 13 March.) Quite what the turnout will be is an altogether different issue with so much other background noise over the last few weeks making it difficult for voters to hear the campaign going on.

Municipal elections matter to the French. My rule of thumb when talking about them to my students is that, while in Britain the overall turnout is about 30%, in France that is the general abstention rate. Well, okay, in the big cities turnout is around 55-60%. In rural communes, the turnout (taux de participation) can be considerably higher. In La Chapelle-aux-Saints, an agreeable and rather dispersed village on the edge of the Corrèze and the Lot where Fifth and a Half happens to have a modest abode, the turnout among the 211 électeurs in 2014 was 86%. The term commune, by the way, has nothing to do with tree-hugging hippy **** nor with radical left-wing politics or any of that sort of malarkey. It is simply the smallest unit of local government in France, although some communes are much bigger than others. Basically, when the French Revolutionaries were redrawing the administrative map of France, they used the old parishes as the lowest level of jurisdiction, shifted a few boundaries here and there and relabelled them as communes. The adjective that is used to describe their election, however, is municipales and not communales. So now you know.

In this blog I’ll explain how the elections work. I’ll look at the political stakes in a later post.

Each commune has a local council whose size is determined by its population, on a sliding scale outlined below.

Altogether, the process will involve the election of more than half a million councillors, but there are two methods of election. In communes of up to 1,000 inhabitants, election is by majority system where candidates can stand on a list or indidividually. The lists are not, however, blocked, and voters can express their preference for candidates from different lists or for individuals. If the requisite number of councillors obtain more than 50% of the vote in the first round, there is no run-off, but if any seats remain to be elected - by no means an unsual situation - voters are summoned to fill the remaining seats a week later.

In communes of 1,000 inhabitants or more, a system that looks like PR is used, but don’t let that fool you. In reality, it is a majority list system with a dose of proportional representation: the list that wins, whether they get an absolute majority in the first round or a relative one in the second, is awarded half the seats on the council. Only then are the remaining seats shared out among all the lists, using the D’Hondt method of the highest remaining average and on condition that they receive 5% of the votes cast. If no list wins an absolute majority in the first round (and that’s the norm given the fragmented nature of French politics), then any list that gained 10% in the first round can stay in the race, while candidates on lists that gained at least 5% of the vote can merge with others. (In these communes, the rules on parity apply, so the lists must alternate between female and male candidates or vice versa, depending on who is the tête de liste. This is not the case in the smaller communes.)

By way of a very rapid illustration, the table below shows how the system played out in Nice in 2014, where eight lists from the first round were reduced to four in the second, competing for 69 seats on the municipal council. Christian Estrosi’s right-wing Union de la Droite list (aka Ensemble pour Nice) had taken 45% of the vote in the first round and increased its share to a shade under 49% in the second. But as the table shows, the consequence of the system was that the ruling group took 52 seats on the city council and 49 on the conseil communautaire serving the ‘greater Nice’ area.

These are the general rules that apply to all 34,968 - or at rather 34,862 - there are 106 were there are no candidates standing, which means the departmental prefect’s office has to step in and administer the commune. There are three exceptions. Lyon, Marseille, and Paris are subdivided into arrondissements or secteurs and councillors are elected at the same time for these district councils as well as the overarching city councils. In Paris, for the first time, the central 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th arrondissements will operate as a single electoral district and elect a single council, the other 16 will continue as before.

Meanwhile, down in Lyon, something new will be happeneing. Voters in the ancient ‘Capital of the Three Gauls’ will vote for their arrondissement councillors, and a portion of these will sit on the city council, the number depending on the population of their district. But voters in Lyon and 58 other surrounding communes will be casting a second vote for the new metropolitan council of ‘le Grand Lyon’ - greater Lyon.

Oh, and on account of Brexit, nearly 600 British nationals who sat on various outgoing municipal councils will not be able to stand again…

A suivre…