Les européennes - prelude to Macron Acte Deux

I’ll be honest. I was not all that optimistic about the turnout ahead of Sunday’s European elections in France. This year, 26 May marked the Fête des Mères and I had visions of carloads of French voters heading off to chez jolie-maman, via the boulangerie to pick up dessert rather than the polling station. Ahead of the election, opinion polls were predicting a better-than-normal turnout – something of the order of 45%. On Friday evening, pretty much the last sondage was suggesting 47%. Imagine everyone’s delight, then, when at lunchtime, French radio stations and news channels were suggesting a turnout that pointed towards above 50%. Whatever one might think about French disaffection with mainstream politics (as opposed to the gilets jaunes), clearly half the pays légal thought it worth their while to drop into the mairie to pop their envelope in the perspex box.

In the end, the taux de participation was just a shade over 50%. How does this compare with previous European elections? Pretty well. My ‘go-to’ for election statistics is the france-politique website maintained by Laurent de Boissieu, journalist with La Croix and a commentator whose Twitter feed is also worth following. The figures can be found here. The first European elections in 1979 saw a 61% turnout. This dropped to 57% in 1984, 49% in 1989, rose to 53% in 1994 before dropping down to 47% in 1999, 43% in 2004, 41% in 2009, before a small rise to 42% in 2014. An hour before the first estimates of the results arrived, we were told to look out for 52% turnout. In the end, it was 50.12% nationally. How might we explain this?

There are a number of factors. The gilets jaunes movement is certainly one of them. While the yellow vest lists did poorly - most voters who identified themselves as supporters and who said they would vote, indicated that they would vote for more ‘conventional’ list – the social crisis has had an impact.

Climate change politics also has clearly had an effect – the late surge by Les Verts, which I’ll come back to in a moment, lifted the turnout.

There is also something to be said for the form and the timing of the election. By the hazards of the electoral calendar, this is the first electoral test for Emmanuel Macron. European elections always fall two years after the presidential elections, but his two immediate predecessors - Nicolas Sarkozy (2007-2012) and François Hollande (2012-2017) - both had to negotiate nationwide municipal elections before the European ones. Sarkozy had not been in office a year before the French told him what they thought of the Président Bling-Bling in les municipales in March 2008. And while le Président Normal had a little longer to prepare, the same happened in March 2014, a couple of months before the European elections. Both were used by the electorate as votes sanctions against the President. (And if you think municipal elections do not matter in France, you really have a great deal to learn.) So, as a first test, the Macron list and his ‘pop-up’ party did reasonably well.

The final factor is the return to a national vote. In 2004, 2009 and 2014, the French used a system of super-regions, not unlike the British system, but unique to European elections. The system was introduced in 2003 by the then PM Jean-Pierre Raffarin and interior minister Sarkozy as a means of damage limitation for Jacques Chirac’s presidential Union pour un Mouvement Populaire, although it failed in that regard. And, on the whole, ruling majorities do not do well in European elections. By my reckoning, the ruling parliamentary party or coalition (NOT the presidential party) has only ‘won’ the European elections on four occasions (1979, 1994, 1999 and 2009). And even then, the results have to be unpacked a little… another time.

The rate of participation/abstention was not the same everywhere, however, and there were some very wide differences in metropolitan France, ranging from a low of 40.8% of abstention to nearly 62% in Corsica and nearly 60.5% in the Paris suburban department of Seine-Saint-Denis. (The official results by department can be found on the Interior Ministry site here.) (In overseas France, the rates of abstention were considerably higher.)

Figure 1 - Le Monde, 28 May 2019

So much for the turnout, Paul. What about the results? Well, here’s a graphic from Le Parisien:

Figure 2 - There were 34 lists - these are the ones that secured more than 1% of the vote. Lists over 3% are eligible for reimbursement of their election costs, but only those over 5% get seats.

The campaign had hardly set the electorate on fire. In the context of the yellow vests movement, the Grand Débat National and Macron’s proposals in response to that, the elections had really taken a back seat until the last couple of weeks, when it became clear that both Marine Le Pen and Emmanuel Macron were going to reduce/elevate the process to a duel between them and their two parties. In that respect, the election turned out as we expected, with Le Pen’s rebranded Rassemblement National-led list winning the largest share of the vote, at 23.3%. Unlike 2014, when she had no national seat in parliament and therefore headed the campaign, Le Pen was not up for election, but installed as tête de liste her new protégé, the 23 year-old Jordan Bardella.

The choice of Bardella was very much hers, and so, in terms of the internal dynamics of the RN as well as national politics, it was important for the list to finish in first place. Mission accomplished then. Finishing second to the Macron list would have been a serious blow to Le Pen, given the wider context of social discontent and doubts within her movement of her ability to win an election in the wake of 2017. Bardella’s youth also points to a young figure being groomed for the succession and challenge to the lurking presence of Marion Maréchal in the background. Domestically, then, the result has shored up Le Pen’s position within the party as well as establishing her and the RN as THE opposition to Macron.

And therein lies the rub. Since the results were announced, various commentators have taken the line, in France and across Europe in general that ‘the far-right populists didn’t do was well as expected’. Perhaps not. But they are now a feature of mainstream politics, not the periphery. Thus, while we can point out that Le Pen’s FN/RN did better in the 2014 European elections (first with 25% of the national vote) and in the 2015 regional elections (first again nationally with 28% of the vote), this result shows that the French far-right have consolidated their position geographically. This is not just a party getting huge votes in certain areas - see Figure 3 below. It is, moreover, a party that mobilises its troops. Something like 80% of those who voted for Le Pen in 2017 turned out to vote, compared to only 54% of macronistes and barely one-third of Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s voters from 2017. (In figure 3 below, communes that voted RN are in pink, LREM in orange. This is a little confusing, because traditionally pink is the colour of the left-wing PS, but that’s Le Figaro for you. Le Monde uses brown…)

Figure 3 - the results by commune from Le Figaro - don’t you just love GIS electoral mapping software?

It’s unusual for a President to get quite as involved in a secondary election as Macron did, but the situation is unusual, and it should not be forgotten that La République en Marche (LREM) remains a work in progress. The wider political context forced his hand and it became inevitable when he launched the Grand Débat and became heavily (perhaps too heavily) implicated in that. His choice of Nathalie Loiseau, the European affairs minister, as tête de liste may or may not have been a good one. She didn’t perform terribly well in the pre-elections debates, but she was by no means the worst. The opinion polls had the LREM and their allies more or less neck and neck with the RN until the last ten days or so, when the RN crept ahead. It’s always risky turning an election into a plebiscite, but Macron had very little choice. In the event, the result was better than it might have been. However, as PM Edouard Philippe said on Sunday evening, ‘if you come second, you haven’t won’. (Wise words, Ed.)

It was the results behind LREM that were the shocks and, in a sense, a pleasant surprise for Macron (and to some extent Le Pen). Paris Match’s survey of opinion polls had third place going to the maintsream right-wing party, Les Républicains (LR), credited with 14% of voting intentions. That had been the ball-park figure throughout the campaign and at party headquarters on the Rue Vaugirard there was a general feeling that, as with the Fillon campaign in 2017, a late tailwind might even push the list, headed by François-Xavier Bellamy, through the 15% barrier. There was general consternation, when the first exit polls released at 8.00 pm put them in fourth with less than 9% and that is where they stayed. So much, then, for the party that, in late 2016, was a shoo-in for the Elysée.

Just as these elections were always going to be a stern test for the new LREM, just so they would be for the president of LR, Laurent Wauquiez. Elected at the end of 2017 (see my blog entry for 14 December 2017), the president of the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region has been heavily criticised from within his party for taking the LR down the path of identity politics, stigmatised by the wonderfully sardonic Edouard Philippe as the droite Trocadéro. Wauquiez chose Bellamy as tête de liste as a copy of himself (on Bellamy see Arthur Goldhammer’s excellent comment here) rather than a leader who would reach out across the famille de la droite et du centre, but in truth the family needs to take a long hard look at itself. Although LR has 100 deputies in the National Assembly and controls the Senate, the party has still not come to terms with its response to Macron and on Sunday that showed, as disaffected centre-right voters supported the LREM list and not Bellamy.

Wauquiez’s critics within LR, particularly Valérie Pécresse, president of the Ile-de-France region and Gérard Larcher, speaker of the Senate, wre not slow to voice their views. In the opinion of the former, Wauquiez had no option but to resign. If Larcher, by virtue of his office the deuxième personnage de la République was marginally more circumspect in public, in private he has echoed Pécresse and, using his position as speaker has begun to try to rally the right and centre-right ahead of next year’s now critical municipal elections. Apart from its homelands in the Massif Central the LR electorate was virtually invisible and many of its voters simply stayed at home, especially in eastern and south-eastern France. Don’t let Figure 4 below fool you. The scores in departments like the Alpes-Maritimes (Nice) were appalling.

Figure 4 - Le Monde, 28 May 2019

Les Républicains switched places with Les Verts (EELV), the Greens, led by Yannick Jadot. Credited with perhaps 8-9% of the vote by almost every opinion poll, they were boosted by a last minute vote (according to reports 25% of EELV voters decided to vote Green at the very last minute). But let’s not get ahead of ourselves here. While ecology is undoubtedly part of the zeitgeist, we have been here before. I can remember the 1989 election, when the Greens made their ‘breakthrough’ with 11%, only to then slip away in 1994. In 2009, they took 16.28% of the vote, just behind their future allies the PS. It was on the basis of those results that François Hollande promised them seats in the National Assembly, brought them into his electoral coalition in 2012 and they responded by running a very poor candidate, Eva Joly (fine person, poor candidate). In 2014 and out of government they slipped back below 9%. And in 2017, Jadot (very foolishly) stood down in favour of the doomed PS presidential candidate Benoît Hamon. Jadot’s success is in part thanks to the failings of the moderate left, but also to disaffection among ecologist voters with Macron, disappointed by the limitations of his policy, embodied by the resignation of environment minister Nicolas ‘sort of the French David Attenborough’ Hulot late last summer.

Figure 5 - Allez les Verts… until next time. Le Monde 28 May 2019

It’s worth noting the strength of the Green in Brittany the Alps and the southern Massif Central, as well as, for the first time ever, Corsica, where Jadot’s list polled 22%, behind the RN on 27.7%, but well ahead of LREM on 15%, a reflection of what Corsicans see as Macron’s high-handed attitude to their ‘sensibilities’.

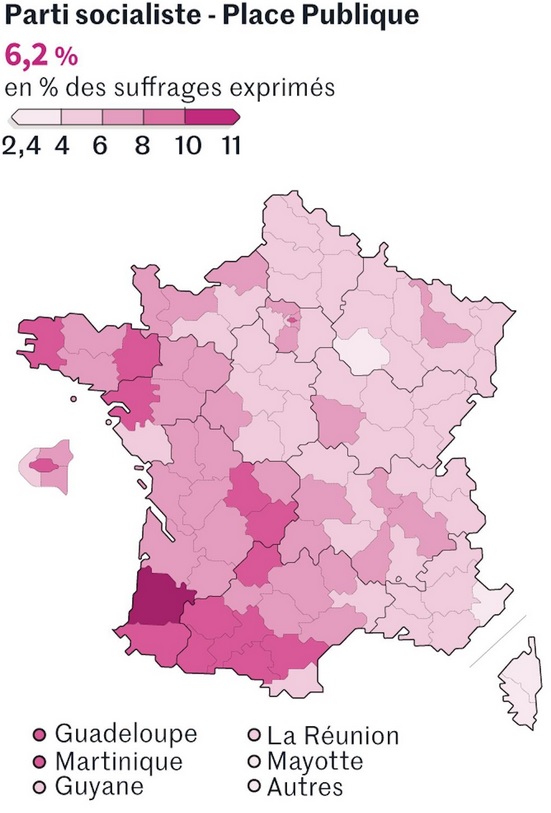

In France, the Greens are generally considered to be on the left, and their success is in some way accounted for not just by dissaffection on the left of the LREM (some 17% of EELV voters on Sunday voted Macron in the first round in 2017) but also frustration with Hamon, Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s La France Insoumise (from 19% to 6.3% for heaven’s sake), and to a lesser degree with the Parti Socialiste. Of these, at least the latter, led by Raphaël Glucksmann (PS-PP), held on to the same proportion of the vote as its candidate (Hamon) did in 2017, while Hamon managed a shade over 3% and at least gets his election expenses reimbursed. As Figure 6 below shows, the PS can still count on its Breton and south-western heartlands. (Raphaël Glucksmann is a philosopher who set up Place Publique as a pro-European centre-left party outside the PS but also to counter the influence of Mélenchon’s La France Insoumise.)

Figure 6 - La gauche cassoulet is alive - Le Monde, 28 May 2019.

Over-optimistic French left-wingers picking over the results were excited to point out that if one added Jadot, Glucksmann and Hamon’s voters together, they would be neck and neck with Loiseau. And if one could persuade La France Insoumise (LFI - led in the election by Manon Aubry) plus the Communist Ian Brossat to join, then that took them past the 30% marker. But that sort of wishful thinking has no basis in political reality.

Where did it go wrong for Jean-Luc Mélenchon and the insoumis? Surely the natural party of the gilet jaunes, instead it seems that, if the yellow vests voted for any party in particular, it was the Rassemblement National. From 19% in the first round of the presidential election in 2017 to less than one-third of that score in 2019. Within the party, patience has begun to run out, not least on the part of deputy Clementine Autain, exasperated with Mélenchon’s ‘anti-everything’ approach, which seems to boil down to shouting at everyone (my view, not Autain’s).

Figure 7 - LFI - Big in the Ariège, Seine-Saint-Denis and overseas… anorexic everywhere else Le Monde, 28 May 2019

One of Autain’s criticisms of Mélenchon has been the failure, justement, to create an alliance populaire of left-wing parties to challenge both Macron and also Le Pen. And it is true that it is the RN that has strengthened its support among working class voters. But continued weakness of the left offers some hope to Macron.

Macron the candidate, it will be remembered, emerged from the left. Macron the president, on the other hand, has governed, for the most part, from the centre and right. Without going into a discussion of policy we can see this simply by looking at the key ministries occupied by Philippe, Bruno Le Maire (finance) and Jean-Michel Blanquer (education). Sunday’s results to the left of LREM, however, offer Macron an opportunity not so much to shift to the left as to open up the possibilities of a group or even a party of centre-left macroncompatibles to mirror the Agir group in the National Assembly on the right of LREM and Modem and acting as a passerelle for disaffected members of LR. It won’t be easy, but it could well be a feature of Acte II of Macron’s presidency, particularly if he is capable of ‘greening’ his politics.

But one thing is certain in the wake of Sunday’s elections. The old left-right division of French politics is done. The division is now between progressistes et nationalistes if you are Macron and mondialistes et patriotes if you are Le Pen. On 12 June Edouard Philippe will outline the next phase of his government’s work to the National Assembly, ahead of a vote of confidence, thus formally launching the second phase of Macron’s presidency. Meanwhile the parties and politicians will look ahead to and begin to prepare the ground (if they haven’t already) for next year’s municipal elections, which one commentator has described as the ‘most depoliticised’ (apologies for the appalling Gallicism) of the Fifth Republic.That’s not quite true, in fact. Bipolarisation only really hit French local elections in the 1970s. Still… the transformation of the political landscape and other less obvious factors, such as the end of the cumul des mandats, have made local politics a fractured field. A gilet jaune mayor anyone?